The Return of the Cancer: Ethan Zohn Fights Back With A “Magic Bullet”

“YOU HAVE CANCER.”

These have to be some of the most gut-wrenching words a person can hear. Especially if you have been in remission after a particularly difficult treatment regimen that included a stem cell transplant.

What would you think then? Would your answer be…?

I’m not a failure. There are millions of people out there living with cancer and you can still have a fulfilled life. You can go to work, raise a family, charge forward. That’s what I’m doing here.

It would, if you were Ethan Zohn. The winner of Survivor: Africa was diagnosed with Hodgkins Lymphoma in April 2009. Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, is a cancer of the immune system, specifically lymph cells (lymphocytes) found in lymph nodes, spleen, liver and bone marrow. He underwent chemotherapy, but the cancer returned in September 2009 and he had to have high dose chemotherapy, followed by radiation therapy and a stem cell transplant. In January 2010, he was reported as being cancer-free. Zohn had been doing fine since then. He and girlfriend, Survivor winner Jenna Morasca, have a show called Everyday Health, Saturdays on ABC. He’s even been training for the NYC Marathon. However, on September 14,doctors told him that the cancer had returned in his chest.

“It’s localized in my lung area,” Zohn, 37, says. “But it’s good that it’s not all over my body.”

Ethan is now on a new medication called SGN-35 (Brentuximab vedotin, trade name: Adcetris). It is one of a number of drugs that are considered Targeted Cancer Therapy. We’ve talked very briefly about this kind of treatment in our story about Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the “Magic Cancer Bullet” called Gleevec. But a further explanation is probably warranted.

What is meant by Targeted Cancer Therapy?

According to the National Cancer Institute targeted cancer therapies are drugs or other substances that block the growth and spread of cancer by interfering with specific molecules needed for tumor growth or spread. Scientists call these molecules “molecular targets.” By focusing on molecular and cellular changes that are specific to cancer, targeted cancer therapies may be more effective than other types of treatment and less harmful to normal cells.

According to the National Cancer Institute targeted cancer therapies are drugs or other substances that block the growth and spread of cancer by interfering with specific molecules needed for tumor growth or spread. Scientists call these molecules “molecular targets.” By focusing on molecular and cellular changes that are specific to cancer, targeted cancer therapies may be more effective than other types of treatment and less harmful to normal cells.

How do cancer cells grow?

In normal cells, growth, division, and differentiation (a process by which a less specialized cell becomes a more specialized cell type) are highly regulated processes. Cells are told what to do by special molecules called signalling molecules. Some of these molecules—called growth factors—tells the cells to divide into more cells. Others cause cells to stop growing or can cause cell death.

Many signaling molecules, including growth factors and growth inhibitors, bind to receptors on the surface of the cell. In many cases, these receptors must interact with one another before they can become fully activated.

Unlike normal cells, cancer cells display uncontrolled growth control- they can ignore signals to stop growing.

Cancer cells use a number of ways to bypass the normal safeguards so they can grow uncontrollably at the expense of normal cells and tissues. These mechanisms include:

Increased signaling for cell growth

Some cancer cells can make their own growth factors. These growth factors travel to the outside of the cell, where they interact with and activate the cancer cell’s growth factor receptors.

Some cancer cells make more growth factor receptors than normal cells—this is called overexpression. Having more receptors available increases the chances that a growth factor will find its receptor.

Evasion of cell death

In adults, the number of body cells is kept relatively constant. Stressed, diseased, malfunctioning, or irreversibly damaged cells, as well as cells that need to be removed routinely as part of normal growth and development, are all removed by a process called apoptosis, also called programmed cell death or cell suicide.

Cancer cells also often avoid cell death by altering the surveillance proteins that normally detect problems.

Other cancer cells evade destruction by overproducing anti-cell death proteins or by creating mutant proteins that are better at blocking cell death signals.

Increased blood vessel formation

The creation of new blood vessels—a highly regulated process called angiogenesis—primarily takes place during early development, when the circulatory system is being formed. In adults, however, angiogenesis normally occurs only to facilitate wound healing or to support various aspects of female reproduction and pregnancy.

Once a tumor gets to a certain size, it requires a blood supply to continue growing. So, tumor cells must find a way to attract new blood vessels. Many tumors release high levels of blood vessel growth factors that bind to and activate the lining cells of nearby blood vessels.

How does Targeted Cancer Therapy work?

Chemotherapy works by stopping or slowing the growth of cancer cells, which grow and divide quickly. But it can also harm healthy cells that divide quickly, which include cells that line your mouth and intestines, cells in your bone marrow that make blood cells, and cells that make your hair grow. Chemotherapy causes side effects (such as hair loss, anemia, sores in the mouth, and nausea) when it harms these healthy cells.

How much better it would be if chemotherapy only destroyed cancer cells, and left normal cells alone!

That’s where targeted cancer therapy comes in.

As researchers have learned more details about how different cancers grow, they have uncovered the specific proteins and factors that allow cancer cell growth to go unchecked. Many of these discoveries are the results of DNA sequencing of these cancers.

Unlike standard chemotherapy, targeted therapies are designed to interact with specific molecules that are part of the pathways and processes used by cancer cells to grow, divide, and spread throughout the body. Targets are chosen very carefully. When researchers discover a potentially vulnerable molecule involved in a cancer process or pathway, they validate it by doing more research, and then, if all goes well, they design new therapies to disrupt its activity with great precision.

Three types of drugs can be used as targeted therapies—small molecules, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines.

Many targeted therapies are small molecules. Once in the body, most small molecules can easily travel across cell membranes, including the plasma membrane. This means that they can be used to interfere with proteins located either outside or inside the cell. Small molecules are often designed to interact with specific areas of the target protein in order to modify its enzyme activity or its interaction with other molecules.

Many targeted therapies are small molecules. Once in the body, most small molecules can easily travel across cell membranes, including the plasma membrane. This means that they can be used to interfere with proteins located either outside or inside the cell. Small molecules are often designed to interact with specific areas of the target protein in order to modify its enzyme activity or its interaction with other molecules.

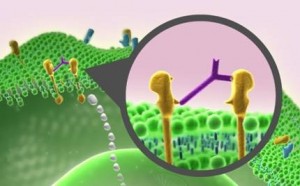

The interaction of signaling molecules with receptors on the outside of a cell often activates pathways inside the cell. Monoclonal antibodies can interfere with these signaling pathways in cancer cells in a number of ways:

- First, antibodies can work outside the cell by preventing signaling molecules and receptors from interacting with each other (1).

- Second, they can also be used as delivery vehicles, guiding radioactive molecules or toxins to the cancer cells (2).

- Third, antibodies attached to a cell can trigger an immune response that destroys the cell (3).

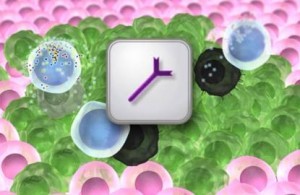

The immune system is programmed to defend the body against invaders, such as a cold virus, but its ability to fight cancer is limited because it doesn’t usually recognize cancer cells as foreign. In fact, some cancers actively suppress the body’s immune responses.Unlike other targeted therapies, therapeutic cancer vaccines do not act specifically on pathways in cancer cells. Instead, they act broadly by trying to activate the body’s immune system to make it recognize and attack cancer cells.

What impact will targeted therapies have on cancer treatment?

Targeted cancer therapies give doctors a better way to tailor cancer treatment, especially when a target is present in some but not all tumors of a particular type. Eventually, treatments may be individualized based on the unique set of molecular targets produced by the patient’s tumor. Targeted cancer therapies also hold the promise of being more selective for cancer cells than normal cells, thus harming fewer normal cells, reducing side effects, and improving quality of life.

Nevertheless, targeted therapies have some limitations. Chief among these is the potential for cells to develop resistance to them. In most cases, another targeted therapy that could overcome this resistance is not available. It is for this reason that targeted therapies may work best in combination, either with other targeted therapies or with more traditional therapies.

Best wishes to Ethan.

0 comments