Jarrius Robertson Receives ESPY Award

Last night, Jarrius Robertson, 15, was awarded the ESPY’s Jimmy V Perserverance Award. Jarrius (known as JJ) is well known in New Orleans as a Saints superfan. But he became known nationwide when he was seen at the NBA All-Star Week held in his home town when he interviewed a number of NBA players. The honorary Saint beefed with Charles Barkley, told Russell Westbrook how to make the playoffs, and got really fed up with journalists stealing his shine when he just wanted to interview John Wall.

But things haven’t been easy for Jarrius. Shortly after he was born, he was diagnosed with a lethal condition of the liver and bile ducts called biliary atresia. He underwent an emergency procedure called a Kasai procedure (see below). But the procedure didn’t work and after multiple surgeries, JJ received a liver transplant before his first birthday. He had many complications after his liver transplant, including pneumonia and a collapsed lung. He even had to be put into a medically induced coma for nearly a year! As his parents, Jordy Robertson and Patricia Hoyal said:

“Five, six times we were told he wasn’t going to make it. Then they told us for the seventh time. He was still on the respirator.”

“We didn’t want to see him suffer no more. So we finally signed the papers to let him go … papers to remove the respirator and let him go.”

But JJ had a different idea about that. When the respirator was removed, he started to breath on his own.

Since that time, besides being a superfan, JJ has been an advocate for organ donation. He started his own foundation “It Takes Lives to Save Lives” to educate people about the importance of organ donation.

The Saints have donated $25,000 to help JJ and his parents cover his medical bills.

In April he underwent a second liver transplant.

What is biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia is a life-threatening condition in infants in which the bile ducts inside or outside the liver do not have normal openings.

Bile ducts in the liver, also called hepatic ducts, are tubes that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder for storage and to the small intestine for use in digestion. Bile is a fluid made by the liver that serves two main functions: carrying toxins and waste products out of the body and helping the body digest fats and absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Bile ducts in the liver, also called hepatic ducts, are tubes that carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder for storage and to the small intestine for use in digestion. Bile is a fluid made by the liver that serves two main functions: carrying toxins and waste products out of the body and helping the body digest fats and absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

With biliary atresia, bile becomes trapped, builds up, and damages the liver. The damage leads to scarring, loss of liver tissue, and cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a chronic, or long lasting, liver condition caused by scar tissue and cell damage that makes it hard for the liver to remove toxins from the blood. These toxins build up in the blood and the liver slowly deteriorates and malfunctions. Without treatment, the liver eventually fails and the infant needs a liver transplant to stay alive.

The two types of biliary atresia are fetal and perinatal. Fetal biliary atresia appears while the baby is in the womb. Perinatal biliary atresia is much more common and does not become evident until 2 to 4 weeks after birth. Some infants, particularly those with the fetal form, also have birth defects in the heart, spleen, or intestines.

Who is at risk for biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia is rare and only affects about one out of every 18,000 infants.1 The disease is more common in females, premature babies, and children of Asian or African American heritage.

What are the symptoms of biliary atresia?

The first symptom of biliary atresia is jaundice––when the skin and whites of the eyes turn yellow. Jaundice occurs when the liver does not remove bilirubin, a reddish-yellow substance formed when hemoglobin breaks down. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein that gives blood its red color. Bilirubin is absorbed by the liver, processed, and released into bile. Blockage of the bile ducts forces bilirubin to build up in the blood.

Other common symptoms of biliary atresia include

- dark urine, from the high levels of bilirubin in the blood spilling over into the urine

- gray or white stools, from a lack of bilirubin reaching the intestines

- slow weight gain and growth

What causes biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia likely has multiple causes, though none are yet proven. Biliary atresia is not an inherited disease, meaning it does not pass from parent to child. Therefore, survivors of biliary atresia are not at risk for passing the disorder to their children.

Biliary atresia is most likely caused by an event in the womb or around the time of birth. Possible triggers of the event may include one or more of the following:

- a viral or bacterial infection after birth, such as cytomegalovirus, reovirus, or rotavirus

- an immune system problem, such as when the immune system attacks the liver or bile ducts for unknown reasons

- a genetic mutation, which is a permanent change in a gene’s structure

- a problem during liver and bile duct development in the womb

- exposure to toxic substances

How is biliary atresia treated?

Biliary atresia is treated with surgery, called the Kasai procedure, or a liver transplant.

Kasai Procedure

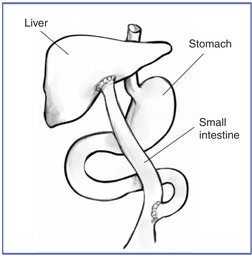

The Kasai procedure

The Kasai procedure, named after the surgeon who invented the operation, is usually the first treatment for biliary atresia. During a Kasai procedure, the pediatric surgeon removes the in

fant’s damaged bile ducts and brings up a loop of intestine to replace them. As a result, bile flows straight to the small intestine.

While this operation doesn’t cure biliary atresia, it can restore bile flow and correct many problems caused by biliary atresia. Without surgery, infants with biliary atresia are unlikely to live past age 2. This procedure is most effective in infants younger than 3 months old, because they usually haven’t yet developed permanent liver damage. Some infants with biliary atresia who undergo a successful Kasai procedure regain good health and no longer have jaundice or major liver problems.

If the Kasai procedure is not successful, infants usually need a liver transplant within 1 to 2 years. Even after a successful surgery, most infants with biliary atresia slowly develop cirrhosis over the years and require a liver transplant by adulthood.

Liver Transplant

Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment for biliary atresia, and the survival rate after surgery has increased dramatically in recent years. As a result, most infants with biliary atresia now survive. Progress in transplant surgery has also increased the availability and efficient use of livers for transplantation in children, so almost all infants requiring a transplant can receive one.

In years past, the size of the transplanted liver had to match the size of the infant’s liver. Thus, only livers from recently deceased small children could be transplanted into infants with biliary atresia. New methods now make it possible to transplant a portion of a deceased adult’s liver into an infant. This type of surgery is called a reduced-size or split-liver transplant.

Part of a living adult donor’s liver can also be used for transplantation. Healthy liver tissue grows quickly; therefore, if an infant receives part of a liver from a living donor, both the donor and the infant can grow complete livers over time.

Infants with fetal biliary atresia are more likely to need a liver transplant—and usually sooner—than infants with the more common perinatal form. The extent of damage can also influence how soon an infant will need a liver transplant.

After a liver transplant, a regimen of medications is used to prevent the immune system from rejecting the new liver. Health care providers may also prescribe blood pressure medications and antibiotics, along with special diets and vitamin supplements.

A Go Fund Me Page has been created to help pay for Jarrius’ medical bills.

0 comments